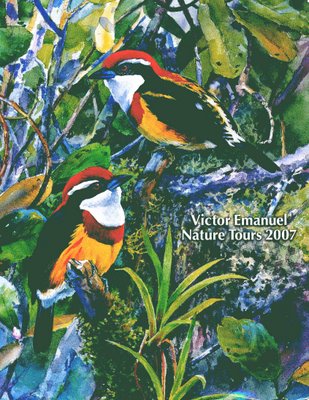

Dumb Luck:

The Discovery of the Scarlet-banded Barbet

by Dan Lane

The following is an account of the Louisiana State University (LSU) inventory expedition to the upper Río Cushabatay in the Cordillera Azul in southwestern Loreto department, Peru in July and August 1996. This was my first visit to South America, and my first time on an LSU expedition. The expedition was organized, funds were acquired by, and the real credit goes to Dr. John O’Neill. I just happened to be lucky enough to be the first person to encounter the new barbet… the story follows…

Expedition member Andy Kratter had been sending letters down with the specimens telling us about the third camp and its avifauna... (roughly paraphrased) "the forest on the camp ridge is quite interesting, but the avifauna is odd. Some of the expected birds such as the included Cyanocorax yncas [Green Jay] are here, whereas others are not. They will finish the trail to the peak of the Cerro tomorrow, and I will go with them..." John was excited by what was returning, as it represented more montane species than what we'd been seeing around Camp 2. He looked forward to the "shipment" from the following day.

Because of how we were spread out, now in three camps, we were unable to spare a nitrogen tank for the third camp to preserve fresh tissues of the birds. Instead, we had agreed that the best plan would be to send collected birds back daily with a Peruvian field hand who would then carry needed supplied (food, ammunition, etc.) back to the third camp the following day. Each shipment accompanied by a note describing the events of the day and the data for the specimens, among other things. Only one collecting ornithologist was at Camp 3 at any one time (until the final week), and we arranged to go up for shifts of one week.

Andy was only able to make it to the peak once in his five-day stay at Camp 3 (a strenuous hike of more than 2 kilometers from the peak). His description of the cloud forest and the montane birds ( Anisognathus somptuosus [Blue-winged Mountain-Tanager], Platycichla leucops [Pale-eyed Thrush], Phaethornis guy [Green Hermit], for example) were cause for great excitement among us "lowlanders" at Camp 2. It was decided that I would be the next ornithologist to ascend to third camp and tackle the peak. I wasn't sure I was ready, but I was looking forward to it in any case. I would be there a week - a week without bathing, a week of heavy hiking, a week of food with no variety but a week full of possibilities!.

My first full day at Camp 3 was a washout with rain all day, but I was able to learn the song of a Tangara tanager which, we were hopeful, was "the new bird of the trip." With the knowledge of this vocalization, we quickly realized how common the bird was in the area. The tanager is a form unknown in Peru, but we would find upon returning to the States that it was nothing more than Tangara varia [Dotted Tanager] of the Guianan Shield of northeastern South America, a range extension for this species of more than 1000 miles!

I climbed the peak my third day at Camp 3. Just at the transition zone on the Cerro (about 1200m) I encountered a lively mixed flock, collecting the trip's first Eubucco versicolor [Versicolored Barbet], and delighting in the many tanagers of various species foraging above my head. Above 1300m, where the true cloudforest began, the species makeup was rather distinct from that on the Camp 3 ridge or the lower ridges by Camp 2. Unfortunately, I had only about three to four hours to explore this strange habitat before having to return to camp.

Two days later (after a day spent on the camp ridge recovering from the hike to the peak), on July 15, I returned to the cloudforest. It was considerably cooler and overcast, the weather apparently not able to make up its mind what to do. I made sure to bring raingear, but was leery of the conditions just the same. The cool temperature, occasional drizzle, and cloudcover seemed to prolong bird activity and I encountered an active mixed flock in the stunted mossy growth of the cloudforest. I turned on the tape recorder while I observed the members of the flock. There was a lot of movement, and it was difficult to remain on a single bird for long, but within a few minutes, I had seen or heard species such as Leptopogon superciliaris [Slaty-capped Flycatcher], Basileuterus tristriatus [Three-striped Warbler], Tityra semifasciata [Masked Tityra], Piranga leucoptera [White-winged Tanager], and Syndactyla subalaris [Lineated Foliage-gleaner], among others. In the middle of the confusion, I caught a glimpse of a bird, or rather, its crown and cheek, but no more. Thinking "hmmmm, what's that?" I noted a red crown, white superciliary, and dark cheek patch. The only thing those marks fit, given what was expected at the locality, was Veniliornis dignus [Yellow-vented Woodpecker], so I decided that's what it must have been. I stopped the tape to identify the voices I had just recorded, and named the other species I had seen in the flock. My attention was grabbed again when a chase broke out between two male Piranga leucoptera [White-winged Tanagers]. I switched the recorder back on. As I taped their chase notes, another bird passed through my field of view and perched in the open right in front of me and proceeded to give some Tityra-like grunting notes. With my right hand, I turned my microphone on the bird as I raised my binoculars with my left.

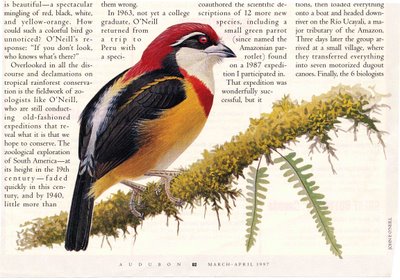

My jaw dropped. It was the bird I had called Veniliornis dignus just a minute before, but clearly it was not a woodpecker. It was a barbet....but one that wasn't illustrated in either the Birds of Colombia or the barbet plate by Larry McQueen for the uncompleted Birds of Peru book (we brought copies of the plates of the latter to "field test" them). I spoke while keeping the mic on the bird, and was amazed to hear how calm my voice seemed "The bird I am looking at now is a new species of barbet..." I started to describe the bird. It was breath-taking: in addition to the afore-mentioned head pattern, the barbet had a white throat bordered with a bold red belt and golden-yellow underparts becoming orangy on the flanks. The back was mostly black with an irregular series of spots of red, then gold, then white, running from the nape to the rump. It had to be a Capito barbet, and somewhat resembled one I remember seeing in the Birds of Colombia. But Peru only has two species of Capito , and we'd already encountered both! This had to be new!

The bird was joined by a second, identical in plumage, and both flew over my head and perched in a tree which was out of reach. I was awestruck and a little disappointed that they were gone. Then one flew back and landed right above me. And then I had it in my hands! Excitedly, I called to Manuel Sanchez, who was just coming up the trail. "Don Manuel, if you see anything that looks like this, COLLECT IT!! It's a new species!" Within two hours, Manuel had acquired two more, and before leaving the cloudforest, I shot a fourth.

I sent the specimens back to John and the others with a note stating in big letters "DO NOT OPEN THIS TUPPERWARE UNTIL YOU HAVE READ THIS!!" The letter attempted to set the scene and break the news gently. I was excited to find, two days later when I returned to Camp 2, that it was indeed a new species.

In the month to follow, a total of thirteen barbet specimens were acquired... mostly by Manuel Sanchez. Andy and I made arrangements to spend a night in a makeshift campsite on the peak and were able to take behavioral notes, get more recordings, and photograph living barbets. Even after we ceased collecting them, the barbet seemed to be quite numerous in the cloudforest, for up to 8 could be seen daily from the relatively small area accessible from the footpath (the undergrowth and lay of the forest preventing much bush whacking).

The main questions that still perplex us are how large is the population of this bird and how widespread are they? The Cerro is not particularly near any other mountains of comparative height, the next nearest peak over 1200m is more than 10 km to the north, and a larger range (disjunct from the Andes) is 40+ km to the west. Do the barbets get that far? In 2000, O’Neill again organized an LSU expedition to the larger range of the Cordillera Azul with finding another population of the barbets one of the main objectives. We spent two months at that site, ascending to 1700 m elevation, but we didn't encounter the barbet. However, we never could reach the kind of tall cloudforest where the barbet was first found so perhaps we were simply in the wrong place.

I am happy to report that Barry Walker, of Manu Expediciones, and some friends returned to the barbet peak in 2002 and found the bird to be very common there. They acquired more tape recordings and video of the species, adding to the store of knowledge on this new and exciting species. In 2000, the barbet was formally described in the Auk (the journal of the American Ornithologists’ Union) having been named the Scarlet-banded Barbet (Capito wallacei)

A Note on Collecting - Collecting figures heavily in this piece and I have made no attempt to soften the reality of a typical South American inventorying expedition. This locality had never been studied by biologists ( The cloudforest on top of the peak on which we discovered the barbet may not have been visited by any humans ever!), so the likelihood of new bird species was good, but without specimens, one would never know! Many species and subspecies are by far more cryptic than our barbet (which, by the way, was not the only new taxon [=a named taxonomic category] we discovered; the others will take more work to verify and probably aren't as exciting), and only by comparing specimens can one confirm their existence.

Specimens provide more than skins for museum collections; the catalogs of vertebrate life on earth. They provide as well information on diet, age, sex, plumage molt cycle, and soft-part colors (for artists), elements not easily assessed without collecting. It would take perhaps fifty hours of intense fieldwork to obtain the same dietary information as the stomach contents of five specimens! Frozen tissues are saved and enable later taxonomic work in the laboratory as well as provide the raw material for toxicological and other environmental studies. Unless there is a vanishingly small number of individuals of a species left in the world, an extremly unlikley event in undisturbed forest, collecting even a moderate series of specimens has little effect on the overall (or even local) population of a species.. In the case of the birds we collected, we determined that, as expected, there was a healthy population of individuals still present after we ceased collecting. Science still needs (and always will need) collections in order to help determine how ecological communities work and, in the end, to save them.